This is a serious moment for our country. Not because America lacks promise, but because it is once again being asked to account for it. Across this nation and around the world, frustration, division, and uncertainty feel familiar, even if the circumstances look new. When I look at what is unfolding in America today, I cannot unsee the patterns history has already taught us to recognize.

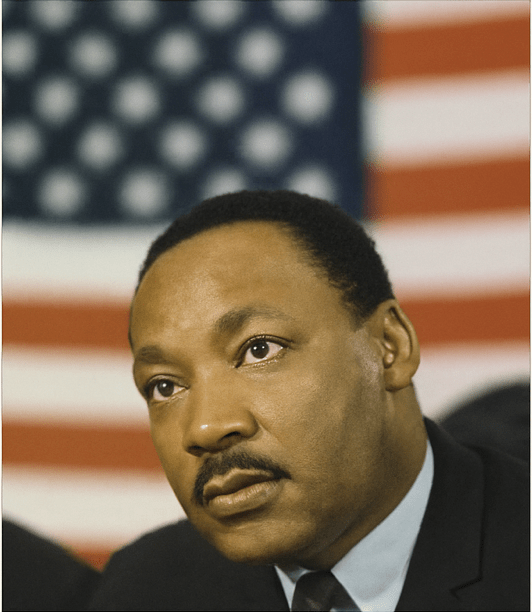

There are moments when the past stops feeling distant and starts feeling present. This feels like one of those moments. It is why I return to the words of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., in his “The Other America” speech in 1967. Not to relive history, but to ask whether we have proven his assessment wrong, or whether we are still living in the America he warned us about.

Dr. King was not speaking to provoke outrage or division. He was speaking as someone who believed deeply in the country and its founding ideals, yet could see clearly that the promise America made had not been kept for everyone. Just four years prior, in 1963, He shared his dream for the country. Over his shoulder as he shared that dream, was President Lincoln’s Memorial, whose Emancipation Proclamation a century earlier in 1863 had begun the formal dismantling of slavery and reshaped the nation’s understanding of liberty and justice for all. Lincoln’s interpretation of the Declaration of Independence extended the promise of freedom proclaimed at the nation’s founding, a promise African Americans had been denied for nearly ninety years after independence. In that moment, Dr. King was not rejecting America. He was challenging it, one hundred years later, to finally live up to what it claimed to be. And now, just over sixty years later, we are still being asked whether we have answered that challenge.

That symbolism mattered then, and it matters now.

After that speech, the country had passed the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act. On paper, progress was undeniable. Daily life told a different story. Jobs were still out of reach for many. Housing discrimination persisted. Schools remained unequal. For millions of Americans, particularly those whose families had lived with the legacy of slavery, equality still felt delayed and conditional.

Dr. King understood why. He spoke openly about how slavery and the violent removal of Native peoples shaped the nation from the beginning. Those choices created systems that rewarded some while excluding others. Even generations later, the effects were still visible in where people lived, the education they received, and the opportunities they were afforded. He warned that progress without honesty, enforcement, and accountability would invite backlash, and that a failure to confront and restrain white supremacy would slow the country down, leaving justice promised but never fully delivered.

Still, Dr. King believed in possibility. From the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, he offered a vision rooted in shared humanity. As he said, “one day right there in Alabama little black boys and black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers.” That vision for America does not belong to some distant past. It is the dream my parents’ generation was raised in, a reminder of how close we still are to this history and how unfinished its promise remains.

That connection feels especially important today.

While Jim Crow laws no longer exist, inequality has not disappeared. In many rural communities, families are still waiting on the investments they were promised. Schools struggle for resources. Infrastructure is outdated. Economic opportunity feels farther away than it should. At the same time, our schools and communities are now more segregated than they were decades ago, a quiet reversal that too few are willing to confront. Too often, instead of addressing these challenges directly, political conversations are redirected toward fear, resentment, and division.

Race becomes a distraction. History is treated as something dangerous rather than instructive. And when that happens, Americans who should benefit from thoughtful, forward-looking policy end up with less. This is not about blame. It is about clarity. We see it in the way the current administration has handled public memory and education, from stripping Martin Luther King Jr. Day of its significance within the National Park Service to replacing imagery meant to honor civil rights progress. Figures like Ruby Bridges and Frederick Douglass are pushed aside, while national symbols are refocused on the Founding Fathers and even the president himself. These choices are not accidental. They reflect how power decides which parts of our history are worth remembering. When we misunderstand our position in American life through fear rather than history, we miss opportunities to move forward together.

Dr. King was urgent because he understood what he was standing up against, but he was also clear about what could not stop the country from moving forward. He spoke openly about backlash, including what he called white backlash, yet he refused to believe it would prevail. He reminded the nation that if the inexpressible cruelties of slavery could not stop the march toward freedom, then opposition in his own time would surely fail. He believed justice would endure because it was rooted not only in protest, but in the sacred heritage of the nation and in a moral demand that could not be erased.

That warning, and that confidence, feel familiar today. The resentment Dr. King spoke about did not disappear after the Civil Rights Movement. It waited. It reshaped itself. And in moments of economic anxiety and cultural change, it has resurfaced. We see it in the way history is debated, in the way fear is used to divide communities, and in the way progress is framed as a loss rather than a shared gain.

Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s legacy in this 250th year of American history cannot be misunderstood. He spoke directly about the same injustices we are now preparing to commemorate as part of the nation’s founding story. We cannot honor his legacy while promoting or legislating against the very efforts he fought for to make life better for those affected by slavery in his time and those still living with its consequences today. What is most sobering is how recent that progress was.

Dr. King was a patriot, and honoring his patriotism must mean more than quoting his words while supporting racism, supremacy, and voided promissory notes. It must mean telling the truth about where we have been and deciding, together, where we want to go next.

That is not about tearing America down.

It is about believing enough in this country to finish the work.

Educator & Future Public Servant

(Inspired by those who led with truth)

Discover more from Three-Fifths

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.