I was sitting in a writing workshop with a group of writers, and our assignment was to make a family tree. We could employ some creative license in making our trees. I set out putting together my creation, complete with an airplane in the sky to show when my parents immigrated from India, to demarcate the generation that moved. Beyond my grandparents, I had blanks and gaps in my tree—I didn’t know who came before: their names, their children, their siblings, or anything about their lives, what they liked to eat, what they did each day.

Once we made our family trees, we were to share our tree with the person sitting next to us. I was seated next to an African American woman from Philadelphia, who had family roots in the south. When we compared our trees, we discovered something we had in common: we both had huge gaps in our family trees.

The gaps in her family trees were due to slavery and family members who disappeared. The gaps in my tree were due to immigration and a lack of information and knowledge about my family ancestry.

But we both had holes.

Knowing our roots is akin to knowing ourselves. There is a certain kind of grounding if you know your roots—and for some folks, a strong sense of pride. But for many of us, that opportunity does not exist, like immigrants, adoptees, Native Americans who were forcibly removed and erased, and those whose ancestors were slaves or indentured.

Black people were forcibly whisked away from their countries of origin and brought to the West to serve as slave labor. They lost touch with their ancestors, their background, their culture, their language, their land, and their roots. And when those ties are severed, there is pain and loss. The removal of a people and the treatment of human beings as property is crushing to the soul and damaging to personhood. It’s inhumane and cruel.

When immigrants come, they leave behind their roots to plant themselves in a new country. It’s a different kind of hole, and sometimes we know our roots and sometimes we don’t. But the common denominator is that they exist, whether we can trace our ancestry back multiple generations or not.

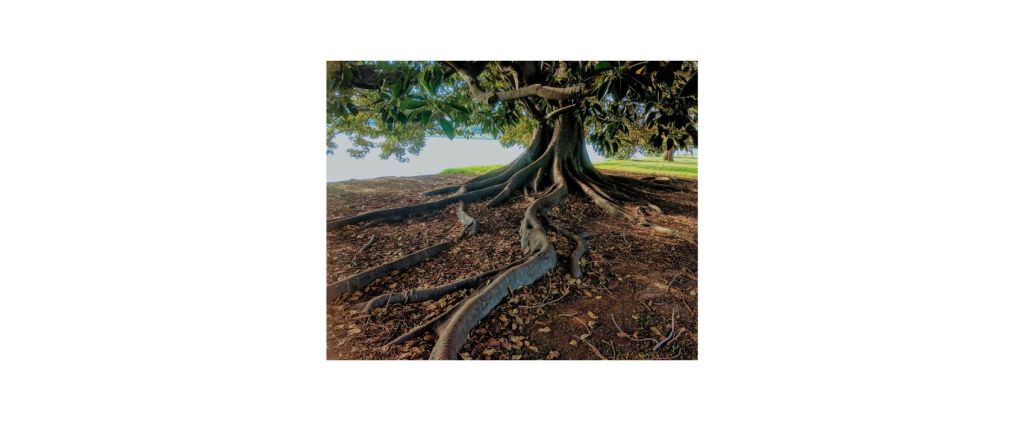

My roots run deep, all the way to another continent on the other side of the world. My roots are from there—and here. It is, in truth, both. Learning my family history and ancestry is a lifelong quest. It requires asking questions, making a family tree, traveling back and forth, and listening and learning. It’s a story still unfolding; or rather, it’s a plant with a root so deep, I haven’t found the end of it.

I grew up in a picturesque valley in the southern Appalachian foothills, surrounded by folks drinking sweetened iced tea and conversations punctuated by “y’all”. Everyone said “y’all” so it inevitably joined my personal vocabulary, too.

Honeysuckle vines grew wild, and as children, we would pull out the delicate flowers and drop the sweet nectar on our tongues. In many respects, moments like these contribute to the files of sweet childhood memories.

But a danger lurked. It was well over a decade since the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and the KKK actively still held meetings in secret places under the shadows of pine trees in my small town. White people still didn’t know what to do with other people who were Black or Brown. The town was segregated.

It’s confusing to say you belong to a place, a place where you’re trying to grow roots and develop community, but you aren’t sure if some in that place really want you. But you still stay and grow—because you know your feet have a right to belong.

Roots are like long extensions of the self. When we don’t know much about our roots, we are missing pieces of ourselves. Having these experiences has made me sensitive and curious about other’s stories. When I look at people around me, I wonder. I wonder about their stories, their histories, their roots, what parts are missing from their stories, and what parts they firmly know. I wonder about their dreams, hopes, and losses. I wonder what brings them joy.

Our stories are connected to our roots, and when those ties are severed, we feel those holes and gaps, those missing pieces of our lives that are lost. But we have hope. We know we belong, that our lives have purpose, meaning, and joy can be restored, even with those voids and ruptures. Our stories, though they may be broken, can be redeemed.

“Maybe you are searching among the branches for what only appears in the roots,” wrote Rumi, a 13th century poet. Sharing the stories of our roots and family trees opened up something in common between myself and someone else in that workshop. Our roots, though we may not have knowledge of their depth or distance or how far and wide they spread, are still attached to this terra firma. If we are on this beautiful earth, we belong here, and we have the capability to offer joy and hope through our presence, our service, our work, our love, our words, and our lives.

By Prasanta Verma

Discover more from Three-Fifths

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.